Prompted by David Riches’ recent find of an early Watkins & Hill proportional divider in nickel silver (aka German silver, aka electrum), I finally got around to writing about another unusual example of the type that came to me via ebay auction (along with an unrelated vernier gizmo) a couple of years back. By coincidence, a related query about the definition of electrum cropped up in the latest UK Slide Rule Circle (UKSRC) Newsletter 70, which circularly linked back to the earlier conversation, so today’s post is doing double duty.

The auction in question had itself appeared in a previous UKSRC Newsletter (48, pp. 36-7), and in retrospect closed rather higher than I would usually countenance for a lone instrument without a case. On the other hand, clearly more than one bidder went through a similar thought process to mine (unless, of course, they were after the vernier gizmo, which further investigation suggests is not entirely implausible, but that’s another story).

For one, the dividers remain the first and only example I have encountered with William Elliott’s Great Newport Street address, occupied early in his career from 1817 to 1827. The end date in particular can be pinned down to within a month, thanks to an Old Bailey court transcript concerning the theft of Elliott’s goods by one of his trusted employees. The testimony begins with a specific reference to his business premises at the time:

WILLIAM ELLIOTT. I am a mathematical instrument maker. I lived in Great Newport-street, at the time of the robbery; I now live in Holborn – the prisoner had been fourteen years in my employ. I placed implicit confidence in him, and treated him like a brother. On Monday, the 25th of June, in consequence of information, I went and searched his house. Mr. Glover and two officers were with me; I there found a quantity of my property. I had never given him authority to take it.

The proceedings took place on 17 July 1827, so Elliott’s relocation must have taken place in the three weeks between 25 June and 17 July of that year. Contemporary references in journals and London street directories corroborate the change in premises. Incidentally, William Elliott comes across very sympathetically in the proceedings, stating that he “did not wish to press the capital charge, as I thought he would be hung if I did”; the 36-year-old James Shaw was ultimately transported for fourteen years.

Returning to the proportional dividers, the Great Newport Street address certainly makes them an early example of Elliott’s handiwork, but this alone was not what grabbed my attention. What did strike me as strange was the material used. To all appearances it was made of German silver, but the prevailing wisdom states that this metal was not used for mathematical instruments until the early 1830s.

As its name suggests, German silver as we know it was first developed in Germany, the result of an 1823 competition to reproduce the Chinese alloy paktong, or “white copper”. The German competition seems to have been prompted by a brief study published the previous year by Dr Andrew Fyfe in the Edinburgh Philosophical Journal entitled “Analysis of Tutenag, or the White Copper of China”, which attracted considerable attention both at home and abroad.

Fyfe apparently considered the terms tutenag and paktong (or, as he would have it, “Pak-Fong”) to be synonyms for the same material. Some of his contemporaries, however, suggested that tutenag referred specifically to a brittle manmade alloy exported in large quantities to India, while paktong was the genuine Chinese “white copper” that was believed to have been smelted from a naturally occurring ore. This latter alloy was so coveted in China that its export was strictly prohibited, although some inevitably made its way to Europe during the eighteenth century (see, for example, Keith Pinn’s 1999 book Paktong: The Chinese Alloy in Europe, 1680-1820).

Fyfe’s sample came from a “basin and ewer” of the material that his friend Dr Howison of Lanarkshire had obtained in China, described as being “of a whitish colour, approaching that of silver […] also highly polished, and does not seem to be easily tarnished”. His chemical analysis suggested that the alloy was composed of 40.4% copper, 25.4% zinc, 31.6% nickel and 2.6% iron, not dissimilar in ratio to the nickel-rich “No. 4” alloy described in this later 1846 article on the various German silver recipes of an unnamed London manufacturer. In China it was said to be valued at about one-fourth of its weight in silver, but clearly the export ban prevented its wider adoption in Europe, hence the desire for a homegrown alternative.

As a result of the 1823 German competition, two manufacturers – the Henniger brothers and Ernst August Geitner – independently came up with viable processes. Geitner was the first to begin commercial production in 1824, under the name Argentan (derived from the Latin word for silver, argentum), while Gebrüder Henniger were hot on his heels with their own Neusilber (German for “new silver”). It was not until 1829 that Percival Norton Johnson brought Geitner’s process back to Britain and began to manufacture his own “British Plate” at Hatton Garden, London, using imported raw materials purchased from Geitner (locally known as Speiss, a waste product of cobalt smelting – see Alistair Grant’s “A British History of ‘German Silver’ Part II: 1829-1924”).

The earliest reference to the use of German silver for drawing instruments that I am aware of is still the 1832 catalogue of Watkins & Hill, who used the term “New White Metal” to describe it, adding that it “does not readily tarnish, and [is] therefore desirable to persons residing in Warm Climates”. Consequently, it would seem reasonable to assume that English drawing instruments of the 1820s or earlier would be made of either brass or sterling silver; the latter reserved for the highest class of instruments, being several times the price of brass. There is no evidence of paktong being used by British instrument makers, probably due to the erratic availability and variable quality of the imported metal.

This all hopefully goes some way to explaining my perplexity upon finding a Great Newport Street era Elliott instrument apparently made of German silver. With the worst-case scenario being that it turned out to be actual silver – a metal Elliott is known to have used in the 1840s, and very scarce in its own right – it seemed worth the gamble that something more interesting might be at play.

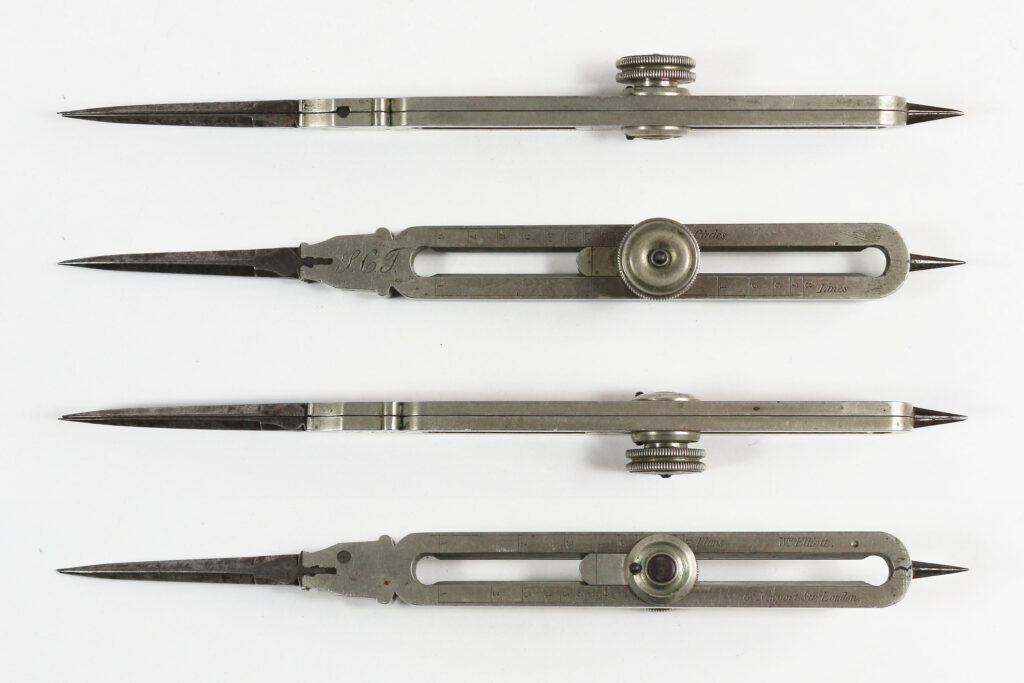

Given the lack of early documentation (the earliest Elliott catalogue I know of dates from 1849, by which time he was using the term “German Silver”), it is fortunate that I had access to a number of other William Elliott proportional dividers with which to compare the Great Newport Street example. Of these, two are German silver and one sterling silver, the latter marked with Elliott’s 268 High Holborn address (1834-49). Of the two in German silver, one is from the brief period during which William Elliott entered partnership with his sons (1850-53), while the other – signed simply “Elliott London” – fits stylistically somewhere between the Great Newport Street and 268 Holborn specimens.

The first thing that struck me was the style of hand-engraved lettering, which is very different on the Great Newport Street dividers to that found on the later Elliott instruments. The characters are small and neat, almost hesitant, compared to the bold, angular script of its three stablemates. Some faintly scribed guidelines can just be made out in places, adding to the overall sense of careful craftsmanship. It is tempting to read it as William Elliott’s own hand, reflecting his apparently fastidious and unassuming personality, but this would be pure speculation; it seems likely that he already had a number of workmen below him at Great Newport Street.

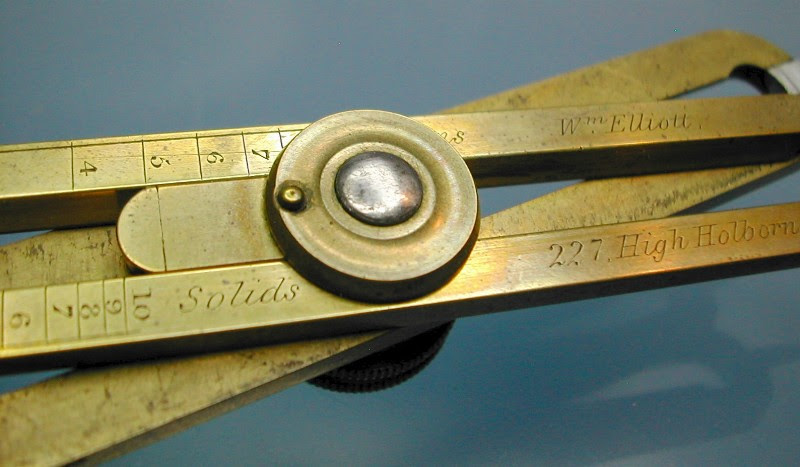

Another feature that marks it out from the others is the presence of “tramlines” to either side of the scales, an early feature generally found on English proportional dividers of the 18th century. These can also be seen on a brass example by Elliott with the 227 High Holborn address (1827-33), suggesting that William Elliott persisted with the older pattern some years into his career (note that the lettering style on this instrument is by a different hand again).

The locking nut of the Great Newport Street dividers (far right of image below) is also noticeably less ornate, a style shared by both the aforementioned 227 High Holborn example and my “Elliott, London” one. The two later dividers both have an extra ridge towards the outer edge of the turned top surface, a trend that continued during the Elliott Bros era with some even more elaborate nut designs.

Between them, the dividers all share a clear familial resemblance, showing a subtle development of certain features over time. This consistency suggests that Elliott had a high degree of control over the manufacture of his instruments for a considerable period of time.

Likewise, the uniformity of engraving on the later examples points to a single source – a theory that David Riches has extended to the proportional dividers from several other “makers” of the early 19th century.

One final clue offered up by the Great Newport Street dividers’ engraving is the monogram “SCT” belonging to a former (original?) owner, deeply cut in copperplate script at one end. This style of monogram has been seen on other proportional dividers by Elliott, which suggests that it may have been a service offered at the point of purchase.

Further correspondence with the seller revealed that the dividers came from a larger selection of instruments all belonging to the same family, some marked “G H Turner” or “GHT”, others “HGT”. While it is difficult to pin down exactly who owned the dividers originally, it seems that the various members of the Turner clan were involved with the armed forces – possibly in India – which could explain the perceived advantage of this new metal, being a prime example of the “Warm Climates” mentioned in Watkins & Hill’s catalogue.

Turning to my observations on the metals used for the four examples in my possession, the Great Newport Street alloy appears relatively soft and malleable compared to the later German silver examples. This is particularly apparent on close examination of surface marks and abrasion (above), in keeping with early reports on the malleability of paktong. What small areas of oxidation are present exhibit the greenish tint of copper alloys, rather than the black of silver.

Overall, the metal is somewhat dull grey in colour, lacking the yellowish cast of the later German silver examples (recall the “whitish colour, approaching to that of silver” of Fyfe’s description). As such, it sharply contrasts with the bright whiteness and high polish of the solid silver dividers, which were most likely lacquered during manufacture and therefore retain much of their original appearance.

The William Elliott proportional dividers are remarkably similar in dimensions, which allowed a rough estimate of their relative density to be obtained by simple weighing (allowing that their steel points may affect the outcome to a small degree). The Great Newport Street example weighed in at 52 g, similar to the German silver version at 50 g. As expected, the solid silver dividers are rather heavier at 56 g. This would seem to be consistent with the typical density of these metals, at around 8.9 g/cm³ for German silver and 10.3 g/cm³ for sterling silver – slightly more than 10% denser, in line with the measured mass of the silver dividers (for reference, carbon steel is approximately 7.85 g/cm³).

In the absence of more sophisticated testing, this suggests three possible sources for the alloy used by Elliott at Great Newport Street:

- German silver obtained from Germany in the first three years of its production

- imported paktong, not previously known for its use in drawing instruments

- an unknown alloy, possibly of British manufacture, but predating Johnson’s “British Plate” (1829)

The final scenario raises another hypothetical scenario: that of Elliott himself experimenting with small batches of alloy, made to his own specifications.

Certainly in later years the firm of Elliott Bros continued as early adopters of new materials – notably aluminium bronze and ebonite, both shown at the 1862 International Exhibition – not least in the race to keep pace with rivals such as WF Stanley who missed no opportunity to remind the world of his own pioneering use of aluminium, Goodyear’s vulcanite and the like.

Elliott’s position as one of the earliest makers to employ German silver was also noted in Stanley Warren and Peter Delehar’s article from the Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society no. 35 (1992). They pointed to its use for an example of Woollgar’s improved plotting scale that carries the 227 High Holborn address (1827-33) and is now in the collection of the Science Museum London.

This particular design of plotting scale was described and illustrated in an 1828 article by JW Woollgar from the Mechanic’s Magazine, which would appear to provide us with an earliest likely date for the instrument. Notably, this source states that:

Mr Elliott, of 227, High Holborn, has had a brass pattern of this scale very accurately laid down, copies of which may be had in box or ivory.

No mention is made of German silver, or any other new white metal; this may reflect the use of these materials still being very much in its infancy. Subsequently, Brian Gee established in his book Francis Watkins and the Dollond Telescope Patent Controversy (2014) that William Elliott had been supplying drawing instruments to Watkins & Hill from the 1830s. It therefore seems probable that just as Watkins & Hill were able to offer proportional dividers in “New White Metal”, so might Elliott to his own customers.

That Elliott was already an artisan of some renown at this point, and no longer simply working for the trade, is supported by contemporary sources such as the Mechanics’ Magazine of 1828 which described him as “Mr. Elliott, the eminent mathematical instrument maker, High Holborn”. By 1849 William Elliott was using the term “German Silver” in his catalogue, but it is not clear if this reflects the source of the material, or was simply the name then in general use. It is worth noting that by the 1860s Stanley favoured “Electrum” for essentially the same material, a descriptor borrowed from the gold-silver alloy of antiquity due to its similar appearance (the word electrum was being used for the nickel-silver alloy from at least 1846).

Just to further muddy the waters, a report on German silver in the Mechanics’ Magazine of 10 April 1830 reads as follows:

The German Silver, which is now coming into vogue, has been introduced, as its name denotes, by the Germans into Europe, but is nothing more than the white copper long known in China. The Goldsmiths’ Company of London have thought it proper to warn the public by advertisements in all the newspapers that it does not contain a single particle of real silver. This is true, for it is only an alloy of copper, nickel, and zinc; but it would have done no discredit to their candour to add, that it is, on account of its perfect unalterability, superior for many purposes (such as musical instruments, touch-holes of guns, &c.) to either silver or gold. Although only now coming into known use in England, it has been no stranger to the manufactories of Birmingham for at least thirty years and more.

The final sentence, at one level a cheap shot at Birmingham’s perceived status as a peddler of low-quality “luxury” goods, may nevertheless reflect a more complex reality on the ground than previously acknowledged. New alloys of all kinds were coming into use in parallel with the improved scientific understanding of metallurgy, not necessarily as a result of it. Commercial imperatives were in some ways a more powerful stimulus to invention than intellectual curiosity.

An example of these unregulated alloys – “no stranger to the manufactories of Birmingham” – may be seen in the early imitations of Mordan’s patent silver pencils from the 1820s, discussed in greater detail towards the end of this post. Though not German silver proper, lacking the essential nickel content, this Birmingham “composition” gives some insight to the metallurgical wild west that was rapidly emerging in the industrial towns of the early 19th century.

Naturally, many questions remain unanswered, not least regarding the precise origin and content of the alloy used by Elliott at Great Newport Street. It would be interesting to discover if recent advances in non-destructive testing (x-ray fluorescence, for example) are able to reveal any more about the composition of these early alloy proportional dividers – “German” silver, paktong or otherwise. Until then, I’m happy to think of them as simply a “new white metal”.